Predictors of posttreatment olfactory improvement in patients with postviral olfactory dysfunction

-

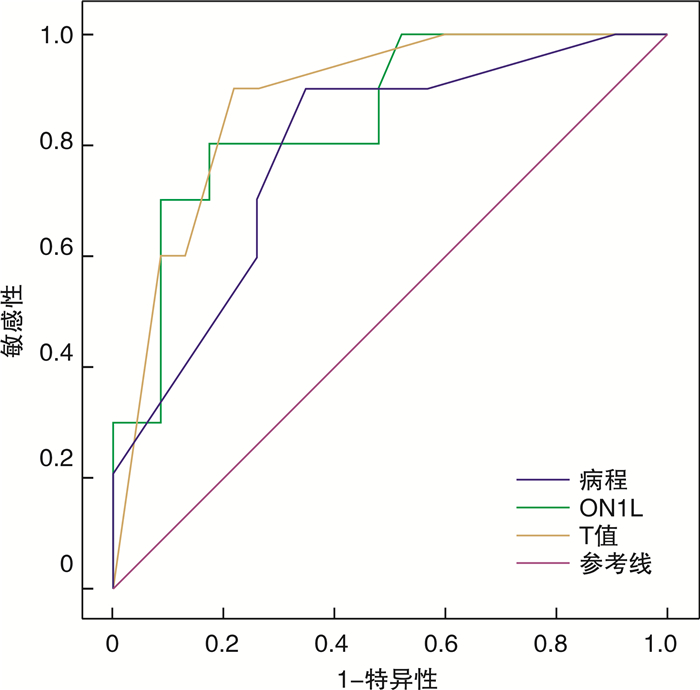

摘要: 目的 分析上呼吸道感染后嗅觉障碍(PVOD)患者主客观嗅觉功能测试结果,评估预后因素,为临床诊疗提供依据。方法 回顾性分析就诊于首都医科大学附属北京安贞医院门诊的PVOD患者,给予嗅觉训练治疗4个月,对患者治疗前后进行Sniffin’Sticks嗅觉测试,根据嗅觉功能改善情况分为嗅觉功能改善组和嗅觉功能无改善组,分析患者一般情况、Sniffin’Sticks嗅觉测试和事件相关电位(ERPs)结果,评估嗅觉预后相关因素。结果 63例PVOD患者的嗅觉改善率为52.38%(33/63)。与嗅觉功能无改善组比较,嗅觉功能改善组病程短(P < 0.001),治疗前嗅觉功能好(P < 0.001),嗅觉阈值低(P < 0.001)。嗅觉事件相关电位(oERPs)和三叉神经事件相关电位(tERPs)的引出率分别为52.38%(33/63)和87.30%(55/63),嗅觉功能改善组oERPs引出率明显高于嗅觉功能无改善组(P < 0.05),而tERPs引出率差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。嗅觉功能改善组oERPs的N1波潜伏期(N1L)和P2波潜伏期(P2L)高于嗅觉功能无改善组(P < 0.05),N1波振幅(N1A)和P2波振幅(P2A)差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。tERPs的N1波和P2波振幅及潜伏期两组间差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。经多因素Logistic回归分析,治疗前阈值(OR=21.376,95%CI:2.172~210.377,P=0.009)、oERPs的N1L(OR=0.994,95%CI:0.988~0.999,P=0.029)和病程(OR=0.607,95%CI:0.405~0.920,P=0.016)与嗅觉预后显著相关。结论 嗅觉障碍病程、嗅觉障碍严重程度、嗅觉功能阈值、oERPs的N1L可作为评估PVOD患者预后的指标。而年龄、嗅觉辨别能力、识别能力、oERPs的振幅和tERPs各波值等对预后评估价值较小。

-

关键词:

- 上呼吸道感染后嗅觉障碍 /

- 嗅觉障碍 /

- 事件相关电位检查 /

- 预后因素

Abstract: Objective To analyzed the results of olfactory function test in patients with post-viral olfactory dysfunction(PVOD), and evaluated the prognostic factors, so as to provide a basis for clinical diagnosis and treatment.Methods This study included patients who were diagnosed with PVOD at least one year ago in Beijing Anzhen Hospital and whose telephone interviews of subjective olfactory function were available. The general condition of the patients, the results Sniffin' Sticks olfactory test and the event-related potentials(ERPs) were analyzed in different improvement groups. This study retrospectively analyzed PVOD patients treated in the outpatient department of Beijing Anzhen Hospital. They were given olfactory training for 4 months. The Sniffin' Sticks test was performed on the patients before and after the treatment. The Sniffin' Sticks test and event-related potentials(ERPs) results were used to evaluate the prognostic factors.Results In this study, the olfactory improvement rate of 63 PVOD patients was 52.38%(33/63). Compared to the non-improvement group, the course of disease in the group with improved subjective olfactory function was significantly shorter(P < 0.001), the initial olfactory function was significantly better(P < 0.001), and the olfactory threshold was much lower(P < 0.001). The presence of olfactory event-related potentials and trigeminal ERPs(tERPs) were 52.38%(33/63) and 87.30%(55/63), respectively. The presence of oERPs in the olfactory function improvement group was significantly higher than that in the non-improvement group(P < 0.05), but there was no difference in the presence of tERPs(P > 0.05). Latency of N1 and P2 waves in oERPs with improvement group(ON1L, OP2L) were longer than those in the non-improvement group(P < 0.05), N1 and P2 wave amplitudes(ON1A, OP2A) had no difference(P > 0.05). The N1 and P2 amplitudes and latency of tERPs showed no difference between the two groups. Multivariate Logistic regression analysis showed that threshold value before treatment(OR=21.376, 95%CI: 2.172—210.377, P=0.009); ON1L(OR=0.994, 95%CI: 0.988—0.999, P=0.029) and course of disease(OR=0.607, 95%CI: 0.405—0.920, P=0.016) was significantly associated with olfactory prognosis.Conclusion The course of olfactory dysfunction, the severity of olfactory dysfunction, the threshold of olfactory function, and the latency of N1 wave of oERPs can be used to evaluate the prognosis of PVOD patients. However, age, olfactory discrimination, recognition ability, oERPs amplitude and tERPs wave value had less prognostic value. -

-

表 1 2组患者临床资料和嗅觉功能比较

因素 嗅觉功能改善组(n=33) 嗅觉功能无改善组(n=30) P 年龄/岁 47.00±11.34 49.47±12.31 0.411 男性 12(36.36) 11(36.67) 0.980 病程/月 3(1~8) 6(2~18) < 0.001 AR 8(24.24) 9(30.00) 0.607 吸烟 10(30.30) 9(30.00) 0.979 治疗前TDI 15.33±4.24 11.00±3.69 < 0.001 治疗前T值 2.58±1.02 1.53±0.59 < 0.001 治疗前D值 6.76±1.80 5.70±1.76 0.022 治疗前I值 6.12±2.09 4.10±1.47 < 0.001 随访TDI 25.55±5.18 13.30±4.00 < 0.001 随访T值 3.96±1.46 1.83±0.74 < 0.001 随访D值 10.97±2.17 6.03±1.63 < 0.001 随访I值 10.94±2.07 5.67±1.90 < 0.001 oERPs引出 23(69.70) 10(33.33) 0.004 oERPs N1L/ms 410.26±62.9 6 507.50±67.90 0.001 N1A/μV -5.17±1.77 -4.90±2.23 0.736 P2L/ms 583.91±74.72 684.90±102.18 0.003 P2A/μV 5.43±2.06 4.50±1.90 0.230 tERPs引出 30(90.90) 25(83.33) 0.367 tERPs N1L/ms 394.68±77.18 438.96±118.16 0.114 N1A/μV -7.16±4.47 -6.96±3.41 0.853 P2L/ms 574.58±92.11 615.12±158.77 0.142 P2A/μV 7.48±3.68 6.64±4.66 0.452 表 2 PVOD患者各因素多元Logistic回归分析

因素 OR 95%CI β P 病程 0.607 0.405~0.910 -0.499 0.016 治疗前T值 21.376 2.172~210.377 3.062 0.009 治疗前D值 1.299 0.208~8.111 0.262 0.780 治疗前I值 2.482 0.872~7.062 0.909 0.088 治疗前TDI 0.717 0.397~1.293 -0.333 0.269 ON1L 0.994 0.988~0.999 -0.006 0.029 OP2L 0.995 0.970~1.021 -0.005 0.715 oERPs引出 0.005 0.000~1703.206 -5.264 0.417 -

[1] Rawal S, Hoffman HJ, Bainbridge KE, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Self-Reported Smell and Taste Alterations: Results from the 2011-2012 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)[J]. Chem Senses, 2016, 41(1): 69-76. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjv057

[2] Hummel T, Whitcroft KL, Andrews P, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction[J]. Rhinol Suppl, 2017, 54(26): 1-30.

[3] Potter MR, Chen JH, Lobban NS, et al. Olfactory dysfunction from acute upper respiratory infections: relationship to season of onset[J]. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol, 2020, 10(6): 706-712. doi: 10.1002/alr.22551

[4] Tian J, Pinto JM, Li L, et al. Identification of Viruses in Patients With Postviral Olfactory Dysfunction by Multiplex Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction[J]. Laryngoscope, 2021, 131(1): 158-164. doi: 10.1002/lary.28997

[5] 田俊, 魏永祥. 上气道感染后嗅觉障碍病因及其致病机制研究进展[J]. 临床耳鼻咽喉头颈外科杂志, 2019, 33(5): 477-480. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-LCEH201905026.htm

[6] Hura N, Xie DX, Choby GW, et al. Treatment of post-viral olfactory dysfunction: an evidence-based review with recommendations[J]. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol, 2020, 10(9): 1065-1086. doi: 10.1002/alr.22624

[7] Damm M, Pikart LK, Reimann H, et al. Olfactory training is helpful in postinfectious olfactory loss: a randomized, controlled, multicenter study[J]. Laryngoscope, 2014, 124(4): 826-831. doi: 10.1002/lary.24340

[8] Konstantinidis I, Tsakiropoulou E, Bekiaridou P, et al. Use of olfactory training in post-traumatic and postinfectious olfactory dysfunction[J]. Laryngoscope, 2013, 123(12): E85-E90. doi: 10.1002/lary.24390

[9] Altundag A, Cayonu M, Kayabasoglu G, et al. Modified olfactory training in patients with postinfectious olfactory loss[J]. Laryngoscope, 2015, 125(8): 1763-1766. doi: 10.1002/lary.25245

[10] Konstantinidis I, Tsakiropoulou E, Constantinidis J. Long term effects of olfactory training in patients with post-infectious olfactory loss[J]. Rhinology, 2016, 54(2): 170-175. doi: 10.4193/Rhino15.264

[11] Kattar N, Do TM, Unis GD, et al. Olfactory Training for Postviral Olfactory Dysfunction: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis[J]. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2021, 164(2): 244-254. doi: 10.1177/0194599820943550

[12] Hummel T, Stupka G, Haehner A, et al. Olfactory training changes electrophysiological responses at the level of the olfactory epithelium[J]. Rhinology, 2018, 56(4): 330-335.

[13] Gellrich J, Han P, Manesse C, et al. Brain volume changes in hyposmic patients before and after olfactory training[J]. Laryngoscope, 2018, 128(7): 1531-1536. doi: 10.1002/lary.27045

[14] Kollndorfer K, Fischmeister FP, Kowalczyk K, et al. Olfactory training induces changes in regional functional connectivity in patients with long-term smell loss[J]. Neuroimage Clin, 2015, 9: 401-410. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2015.09.004

[15] Pekala K, Chandra RK, Turner JH. Efficacy of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol, 2016, 6(3): 299-307. doi: 10.1002/alr.21669

[16] Rombaux P, Huart C, Mouraux A. Assessment of chemosensory function using electroencephalographic techniques[J]. Rhinology, 2012, 50(1): 13-21. doi: 10.4193/Rhino11.126

[17] Gudziol H, Guntinas-Lichius O. Electrophysiologic assessment of olfactory and gustatory function[J]. Handb Clin Neurol, 2019, 164: 247-262.

[18] Kobal G, Hummel T. Olfactory and intranasal trigeminal event-related potentials in anosmic patients[J]. Laryngoscope, 1998, 108(7): 1033-1035. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199807000-00015

[19] Lötsch J, Hummel T. The clinical significance of electrophysiological measures of olfactory function[J]. Behav Brain Res, 2006, 170(1): 78-83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.02.013

[20] Rombaux P, Mouraux A, Keller T, et al. Trigeminal event-related potentials in patients with olfactory dysfunction[J]. Rhinology, 2008, 46(3): 170-174.

[21] Ciurleo R, Bonanno L, De Salvo S, et al. Olfactory dysfunction as a prognostic marker for disability progression in Multiple Sclerosis: An olfactory event related potential study[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(4): e0196006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196006

[22] Liu J, Pinto JM, Yang L, et al. Gender difference in Chinese adults with post-viral olfactory disorder: a hospital-based study[J]. Acta Otolaryngol, 2016, 136(9): 976-981. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2016.1172729

[23] Ren Y, Yang L, Guo Y, et al. Intranasal trigeminal chemosensitivity in patients with postviral and post-traumatic olfactory dysfunction[J]. Acta Otolaryngol, 2012, 132(9): 974-980. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2012.663933

[24] Rombaux P, Huart C, Collet S, et al. Presence of olfactory event-related potentials predicts recovery in patients with olfactory loss following upper respiratory tract infection[J]. Laryngoscope, 2010, 120(10): 2115-2118. doi: 10.1002/lary.21109

[25] Hummel T, Rissom K, Reden J, et al. Effects of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss[J]. Laryngoscope, 2009, 119(3): 496-499. doi: 10.1002/lary.20101

[26] Duncan HJ, Seiden AM. Long-term follow-up of olfactory loss secondary to head trauma and upper respiratory tract infection[J]. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 1995, 121(10): 1183-1187. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890100087015

[27] Mori J, Aiba T, Sugiura M, et al. Clinical study of olfactory disturbance[J]. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl, 1998, 538: 197-201.

[28] Lee DY, Lee WH, Wee JH, et al. Prognosis of postviral olfactory loss: follow-up study for longer than one year[J]. Am J Rhinol Allergy, 2014, 28(5): 419-422. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4102

[29] Reden J, Mueller A, Mueller C, et al. Recovery of olfactory function following closed head injury or infections of the upper respiratory tract[J]. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2006, 132(3): 265-269. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.3.265

[30] London B, Nabet B, Fisher AR, et al. Predictors of prognosis in patients with olfactory disturbance[J]. Ann Neurol, 2008, 63(2): 159-166. doi: 10.1002/ana.21293

[31] Kim DH, Kim SW, Hwang SH, et al. Prognosis of Olfactory Dysfunction according to Etiology and Timing of Treatment[J]. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2017, 156(2): 371-377. doi: 10.1177/0194599816679952

[32] 刘剑锋, 倪道凤, 张秋航. 正常年轻人嗅觉事件相关电位的特点[J]. 临床耳鼻咽喉头颈外科杂志, 2008, 22(8): 352-355. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-LCEH200808008.htm

[33] Rombaux P, Weitz H, Mouraux A, et al. Olfactory function assessed with orthonasal and retronasal testing, olfactory bulb volume, and chemosensory event-related potentials[J]. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 2006, 132(12): 1346-1351. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.12.1346

[34] Liu J, Pinto JM, Yang L, et al. Evaluation of idiopathic olfactory loss with chemosensory event-related potentials and magnetic resonance imaging[J]. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol, 2018, 8(11): 1315-1322. doi: 10.1002/alr.22144

[35] Stuck BA, Frey S, Freiburg C, et al. Chemosensory event-related potentials in relation to side of stimulation, age, sex, and stimulus concentration[J]. Clin Neurophysiol, 2006, 117(6): 1367-1375. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.03.004

-

下载:

下载: